Matrika Devkota overcame a long mental health crisis and is now one of Nepal’s leading advocates for psychosocial rights.

As a young man, Matrika Devkota went through of a mental health crisis lasting almost a decade, costing him his studies and work. But it also led to a valuable insight.

“I used to think mental health problems are diseases like all other diseases. But I discovered they are an issue of barriers, attitudes and isolation”, Matrika says.

After recovering, he decided to dedicate his life to supporting others. He is one of Nepal’s leading advocates for psychosocial rights with a unique perspective to tackling mental health.

“Community can judge, but it can also heal,” he says.

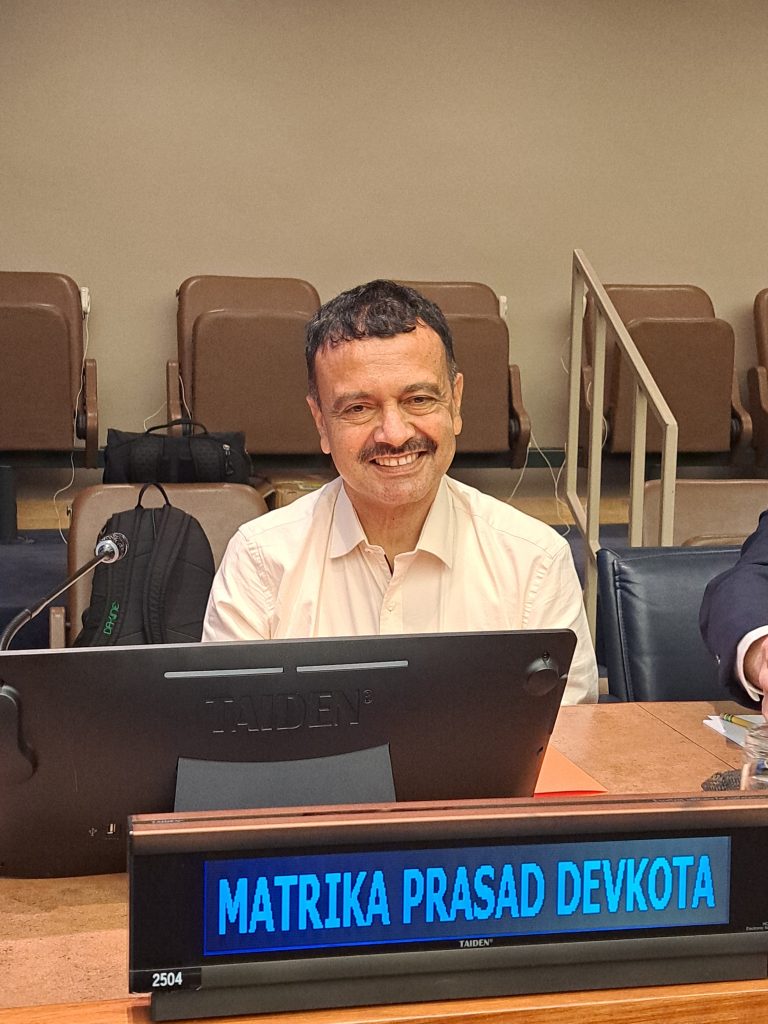

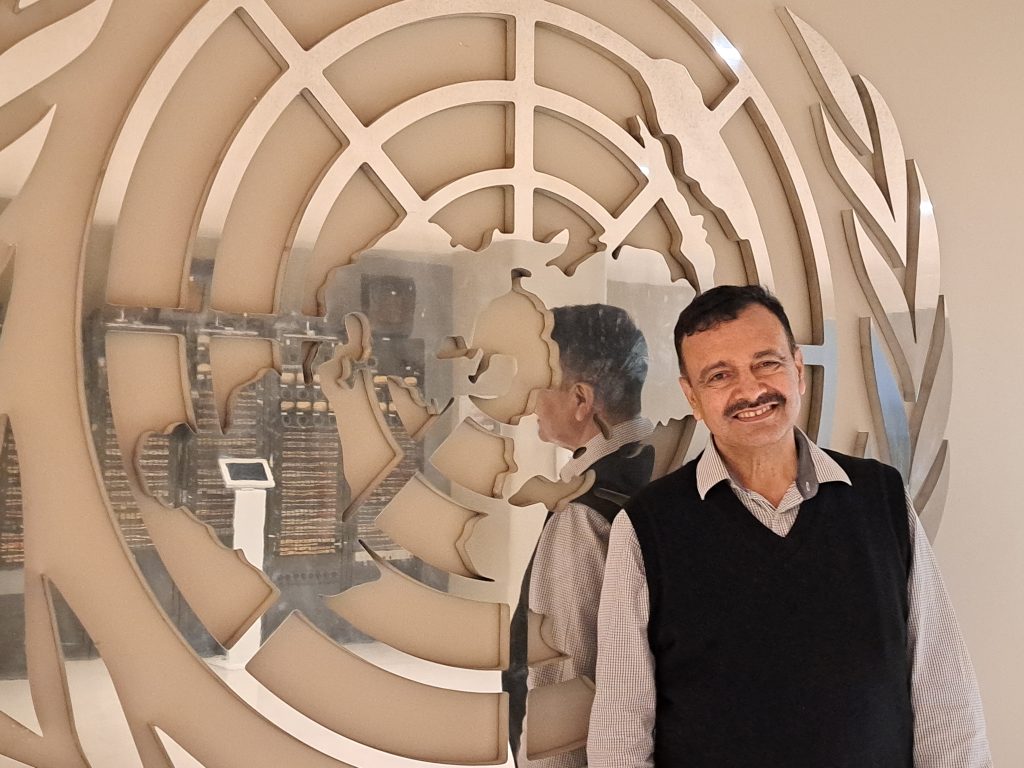

This summer he took that message to New York, where he participated as a representative of Nepal’s civil society at the 18th UN Conference of States Parties to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (COSP18). And he spoke not only of problems, but also solutions and hope discovered in Nepal.

“There are so many solutions that can be scaled up. We are promoting peer groups of people who have gone through mental health problems. They come together and they ventilate. They have started organizing and breaking the silence.”

His organization, KOSHISH, is a long-term partner of Felm, working to address psychosocial challenges in Nepal.

Voice, not silence

In Nepal, mental health challenges often lead to stigma within the community. People facing distress are sometimes seen as dangerous, or as less than fully human.

“We grew up being told that people with mental distress were crazy or unsafe,” Matrika explains.

Matrika’s own story begins in silence. As a teenager, he fell ill with mental distress that neither he nor his family understood. For nearly eight years he was unable to continue his studies or work.

“I used to blame myself, thinking I was the only unlucky person,” he recalls.

Only in his late twenties, after finally finding therapy, did he begin to realize that his suffering was shared by many others. That realization became a turning point. Today, at 54, he leads KOSHISH, Nepal’s first organization of people with psychosocial disabilities, founded in 2008 after Nepal became signatory to the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

This work has given a meaning to the suffering he once went through. He now can draw from his own experience to help others.

“Everything has a purpose,” he says.

Rights instead of charity

For Matrika and his colleagues, the shift from seeing mental health as an illness to seeing it as a human rights issue is crucial.

Nepal’s Disabled Rights Act of 2017 was a milestone: for the first time, psychosocial disabilities were recognized in law. This has meant access to legal remedies, protection against discrimination, and the right to reasonable accommodation in daily life.

Yet the reality is still uneven.

“The laws are beautiful on paper,” Matrika says. “But in practice, changing mindsets takes generations.”

Harsh attitudes towards the disabled are often rooted in religious beliefs. People may be seen as deserving their fate.

“Poor will be poor also after death because it’s karma,” Matrika says, describing the worldview rooted deep in the culture.

Peer groups and collective healing

Despite the many obstacles, change is underway. Old stigmas are giving way as legal reforms and grassroots initiatives begin to reshape attitudes. Dignity and inclusion take root.

In peer groups people with psychosocial challenges meet, share experiences, and break their isolation. This community-based approach has been developed further in joint projects between KOSHISH and Felm.

“The biggest problem is that people think they are alone with their problems. When we share our stories, we also learn empathy — to see our own face in the suffering of others.”

For Matrika, empathy is at the heart of community-based mental health. By recognizing one’s own struggles in the experiences of others, people move from isolation to belonging — from I and they to I and we.

In the global North, he points out, people have social protection, therapies and medication but less time for interaction. In Nepal, the strong community that may be judgmental, can also be turned into a resource for healing.

“Here, people are mobilized by neighbors and networks. There are lots of festival almost every week and people share each other — and less isolation,” Matrika says.

Matrika suggests the individual model of the West for treating psychosocial challenges could be complemented with the community-based approach pioneered in Nepal.

Nepal on the global stage

At COSP18, Matrika shared these lessons with delegates from around the world. For him, being on panels alongside government representatives was a moment of pride.

“Not just people with high degrees or political power, but also grassroots activists could share what we have done on the ground.”

He sees international dialogue as essential. Nepal needs continued support—from funding to technical expertise—but it also has models worth sharing.

“We can show there are possibilities. Not just problems, but hope.”

Despite progress, implementation in Nepal is slow. Corruption, weak state mechanisms, and entrenched attitudes often block real change at the village level.

“Changing the mindset is the biggest challenge,” Matrika admits.

Still, he insists on hope:

“Maybe I cannot do everything in my lifetime. But someone from the next generation will continue.”

For him, the journey is both personal and collective.

“In the suffering of others, I see my own suffering. And I am no longer vulnerable—I have a lot to contribute to my community.”

Text: Taneli Heikka, Senior Communications Specialist, Felm Nepal

Funded by Finland’s development cooperation.